MATCHESS: THE CAIRN AT BISKOPSKULLA-HÖGSTENA

CODDIWOMPLE

SECRET CORNERS

Tales on favourite spots by our network of fem人le musicians

MATCHESS

THE CAIRN AT BISKOPSKULLA-HÖGSTENA

At the start of 2022, I moved into a barn in rural Sweden. The village of Biskopskulla-Högstena has six properties, my few neighbors during the Nordic winter. I brought my viola, lightweight electronics, recording equipment, and some warm clothes, thriving on a diet of pickled fish, hard bread, and candy. When I arrived, the sun came up around 9:00 AM and went down at about 3:00 PM. Snow covered the fields at first, but I started to find some amazing rocks on my daytime walks around the village, forests, and countryside. Many of these moss- and lichen-covered boulders stand alone, some lie in stacks, and other giants cascade as cliffs.

It was difficult to tell which stones sat eternally untouched and which had been moved by human hands. I visited Anundshög, where Vikings had built a large tumulus over a crematorium. Stone ships were arranged beside the massive grave.

Closer to the village, along the road to the nearest town of Örsundsbro, I came across a rune stone.

Eureka! What deep pleasure I felt while beholding this ancient carved stone standing amidst the plain fields.

The inscription had been carved between 725 and 1100, reading, “Gísl and Ingimundr, good valiant men, had the landmark made in memory of Halfdan, their father and in memory of Eydís, their mother. May God now help her soul well.” I visited the stone at night.

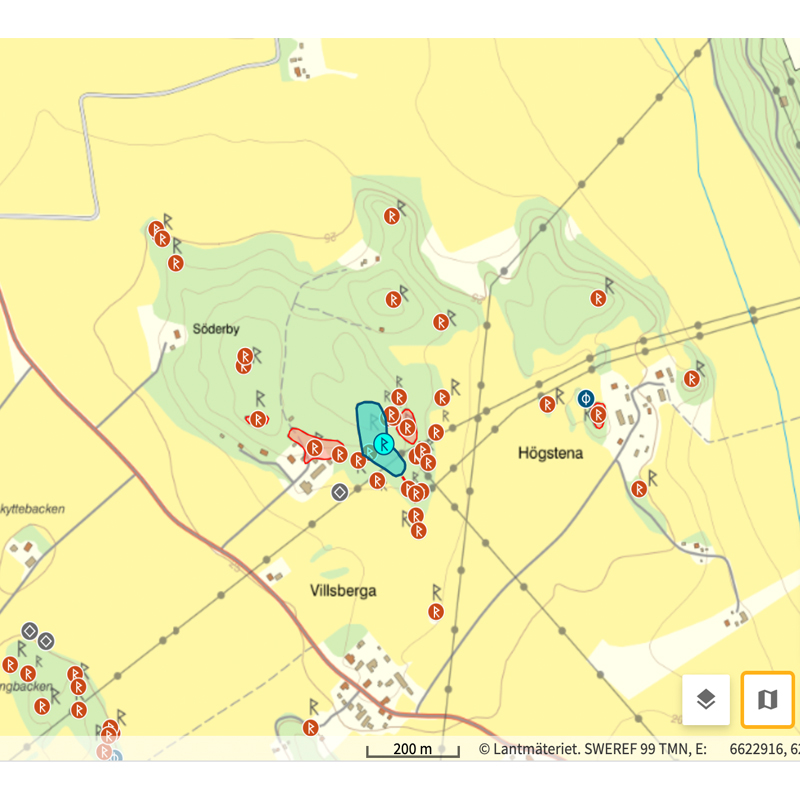

With treasured rune stone #808 so nearby, I wondered what other amazing rocks were around the barn. With a little looking on the computer, I discovered a detailed map by the Swedish National Heritage Board. They seem to have documented every stone. Scanned pages from notebooks include drawings, descriptions, hand-drawn maps, and archaeological fieldnotes.

When I located the village, it turned out to be full of significant stones, many of them marking graves. In fact, a burial mound was situated right next to the barn, though it’s a little hard to see through the trees.

Living alone in the country was frightening, especially coming from a city like Chicago. Instead of hearing voices and cars through the day and night, I heard the barn creaking, rodents in the walls, and wind rattling the roof. According to probability, Chicago is much more dangerous than a Swedish village, but my nervous system didn’t get the message. After a few days, I felt comfortable sleeping in the loft, but at night I always felt like someone was standing in the dark watching me through the windows. In fact, on a night with fresh snow and a bright moon, I heard voices. It turned out to be my neighbors taking a walk by the burial mound.

Despite my list of books in hand, I spontaneously picked up Killing Commendatore by Haruki Murakami in the English-language section of the bookstore. In this novel, an artist breaks up with his partner and moves alone to a house in the country. I could relate with everything in the premise. Without spoiling anything, let me say that the artist finds an assemblage of big stones nearby the house. In that region of Japan, stones like these had sometimes been arranged into a living tomb, a chamber for an elderly Buddhist monk on the verge of enlightenment to be buried alive in the practice of Sokushinbutsu. The monk would ring a bell in the chamber while alive, and initiates would listen for the ringing to stop. When they opened the tomb, the monk’s body would have been mummified. As I explored the burial mound beside the barn, I found an arrangement of large stones on top—maybe a wall, maybe part of a building, or maybe a part of the burial structure I imagined in the book. Sometimes I lay awake listening for the sound of a bell.

Anyway, there were amazing rocks all around me. I had to see more of them. On the dirt road leading up to the village was another, smaller dirt path. The map told me there were lots of amazing rocks nearby some electricity towers, so I embarked in that direction. After a few minutes walking, I noticed a couple red dots in the snow, then a few more, then lines of red. A trail of blood. And a single pair of boot prints. I kept walking toward the stones, wondering what was bleeding. Most likely, a hunter was bringing home a pheasant or hare. Like a flash of lightning, I became aware that I was walking alone, following a trail of blood toward a burial ground. Ok, I took a photo and got the hell out of there!

As days went by, the temperature started to hover around freezing, thawing the snow in the sunlight and freezing the water at night. It was a slippery mess. I remember one time taking the long, hilly way home from the grocery store. When the one-lane road became a pure sheet of ice, I had to gingerly turn around on the top of a hill, inches at a time. Walking around was difficult, but the right time of day made it possible. I had to get back to the grave field, despite the trail of blood. This time I didn’t see any red on the soggy ground and kept exploring. The rocks were surrounded by power lines, and there was some weird trash around, including an empty bathtub and bundles of barbed wire. In the distance was a barn in disrepair and a farmhouse that looked uninhabited. As I explored these amazing rocks, there it was, before my eyes: the Cairn.

O majesty of time, sculpting each mortal span.

Purest fear resists your magnetism, my passion.

What vaunted chisel would malign?

Whose hubris deign improve,

Dare remove a speck from thy aspect?

Eternal graces, wind and rain

Carve your curves,

Sublime gem sprung from earth.

Lo, fresh vision and bond

To abjure all else

In obedience to thee.

Shaken and changed under the setting sun, I made my way back to the barn. Of course, I couldn’t get the Cairn out of my head that night, but it was also my first thought the next morning. And the coming days were no different. When returning to the barn in the evening, I would stand in the dark, listening for the Cairn, hearing a low hum coming from its direction. The moan of the wind or a machine? Farmers had to work in the dark this time of year. As the days went by, the Cairn loomed ever larger in my mind. Each time I passed in its direction, I wondered if it was real, looked for evidence, listened for the low moan. Sometimes I stopped to visit and listened even closer.

The January blizzards became February rain storms, and then went back to snow and ice again. One night in a downpour, I drove down the muddy road to the village. On the path toward the Cairn, I saw a bouncing light. Someone was walking in its direction, wearing a headlamp in the storm. The jumping beam, leather boots sloshing down the path, following the low moan, the chills down my spine, fear and love and ecstasy.

Whitney Johnson aka Matchess (Clearfield, Pennsylvania) is an artist who interprets the unknown with sound. She composes, improvises, and collaborates with the viola, as well as sine waves, tuning forks, electronics, organ, and vocalization. Her techniques reproduce meaning through a range of historical material processes, including reel-to-reel tape looping, cassette tape sampling, and field recording. Her latest release Sonescent (2022, Drag City) recreates the experience of 10 days of silent Vipassana meditation in Joshua Tree, CA where she heard “the last minutes in the life of music.” Three recent works have engaged with skepticism and belief in the effects of sound on the body. Huizkol (premiered at Lampo), The Tuning of the Elements (curated by the Renaissance Society of the University of Chicago), and Fundamental 256 Hz (commissioned by Longform Editions). In tandem with her sound practice, she received her doctorate in the sociology of sound from the University of Chicago in 2018 and she is currently an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Sound and Liberal Arts at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a postdoctoral researcher on sound and technology in the Centre for Gender Research at Uppsala University in Sweden.