QUINTA: WILD PLACES AND GETTING LOST

CODDIWOMPLE

SECRET CORNERS

Tales on favourite spots by our network of fem人le musicians

QUINTA

WILD PLACES AND GETTING LOST

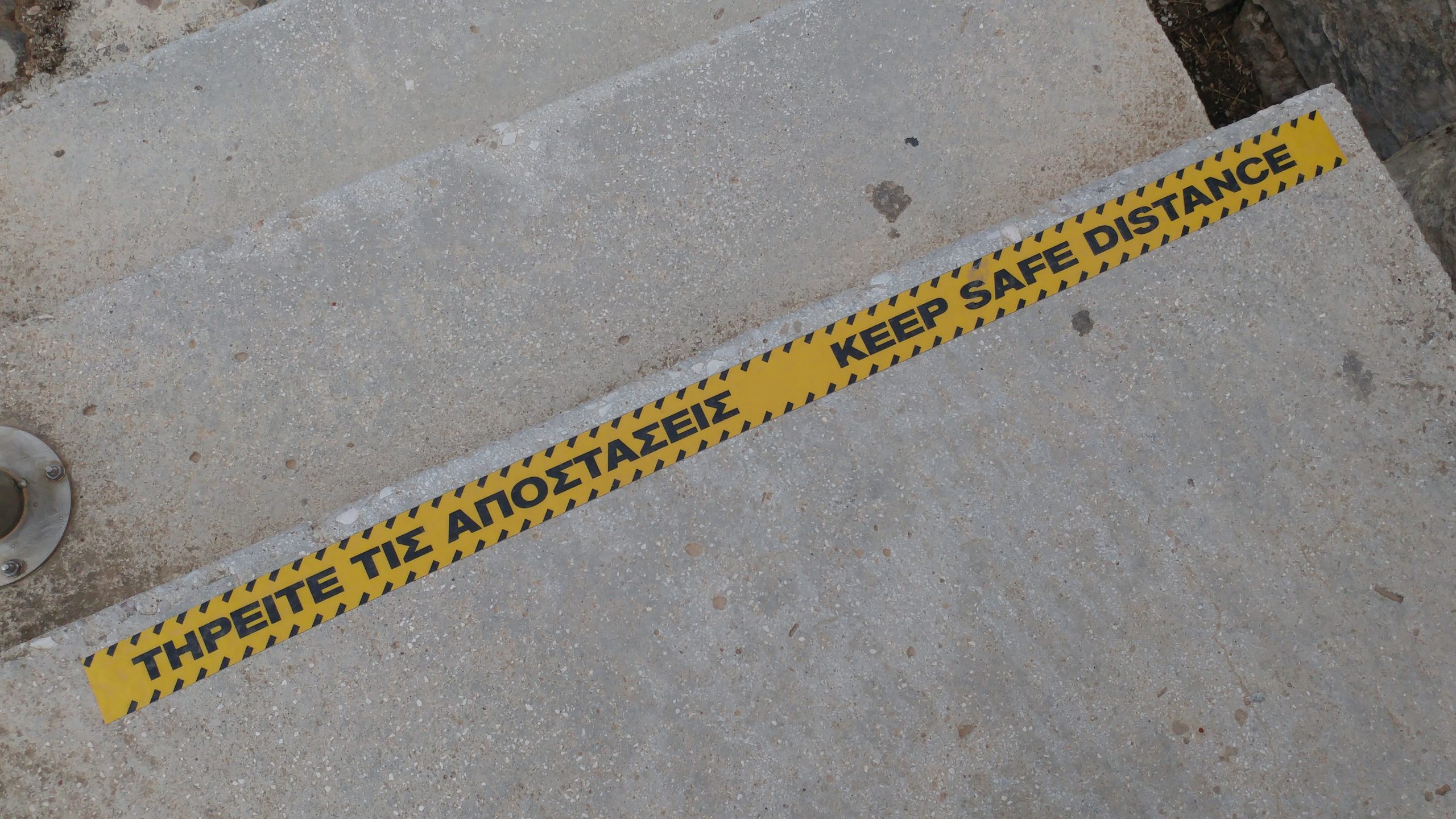

We felt close to the sky that morning, high up on the Athens Acropolis with deep thunder clouds rolling in overhead. Apart from the stewards, possibly one or two other tourists, and some tiny far-off workmen moving across the scaffolding and around the very highest parts of the Parthenon, chisels in hand, endless restorations ahead, we were the only visitors. We sat on a marble bench that felt cool to the touch and gazed at the monuments as the weather moved in. Looking out across the city of Athens from this vantage point on its southern side, we felt the preciousness of this unique moment, but also its strangeness and melancholy.

The coronavirus pandemic had been raging for a number of months and restrictions in Greece had been swift and decisive. Lockdown had meant not leaving our flat without a permit. The empty streets, usually a buzzing riot of cars and scooters, felt like a silent film set. Precarious strings of shoppers, masked and distanced, waited nervously along pavements outside the supermarket. This usually bustling city seemed quiet and afraid. But now it was May and internal restrictions had begun to lift. The emptiness of the iconic place we were now visiting expressed everything about this very singular moment. I’d read an article about another British resident of Athens who’d made a visit to the Acropolis since covid regulations had lifted. . She’d described feeling comforted by the longevity of those ancient stones, especially in such times of uncertainty and dread.

Maybe I’d wanted too much to feel this too, but as I looked up at the stones, they seemed a little sad and a little destroyed- and may be a little censuring too, their longevity standing for something today’s humans seemed to be fast unravelling, hurtling as we were from one deepening catastrophe to the next, seeming intent on undoing all the beautiful things we’d made and fostered on this earth.

Picking our way southward across Europe the previous August, a travelling swansong we hoped would drown out the clamorous pre-echo of Brexit’s closing gates, we’d headed for Athens. I’d wanted to leave behind my familiar work patterns and networks, take a few risks creatively, read, write and play, strip everything away and see what was left. Moving places for a while, I’d thought, might release me. The geographical shift, I’d hoped, would precipitate an interior one.

The weekend we’d visited a virtually tourist-free Acropolis, we’d also gone away camping on the nearby island of Evia. Exploring a new place for us had always meant walking, whether in sandals on the smoothed marble flagstones of the city or in walking boots along the isolated mountain paths of the countryside. That weekend we’d walked such a distance we’d pretty much eaten chocolate cornflake cakes the entire day we got back, as though we’d run a marathon. On the Saturday, we’d scaled Mount Dirfys, Evia’s highest mountain, which, after an initial section through beautiful woodland lit with shards of sunshine, was unrelenting steep stony uphill for two hours. The sun was hot but the air was fresh, especially as the wind began to whip our hair into strings. The top of the mountain was unexpectedly large and flat, with a generous expanse of unmelted snow.

We sat nearby munching kalouria and boiled eggs, then lay down and watched the sky as wisps of white cloud slid rapidly and quietly overhead almost close enough to touch. After half an hour or so, we noticed the temperature drop and the clouds thicken into larger masses that began to block out the sun. Heading down, our hands began to freeze as the whiteness settled around us. We felt very high up and things felt wild. From the top we’d barely been able to see any sign of human habitation in any direction. By the time we got down to the more level section of the path, our legs wobbled and we discussed biscuits.

That night we camped on the beach at Chiliadou, as did a few others, including a group of young people partying, singing Hey-ee-ay-ee-ay, I said hey, what’s going on? high into the night sky. Neither of us felt an inch of complaint. It was a cry filled with something of the moment and we both knew it.

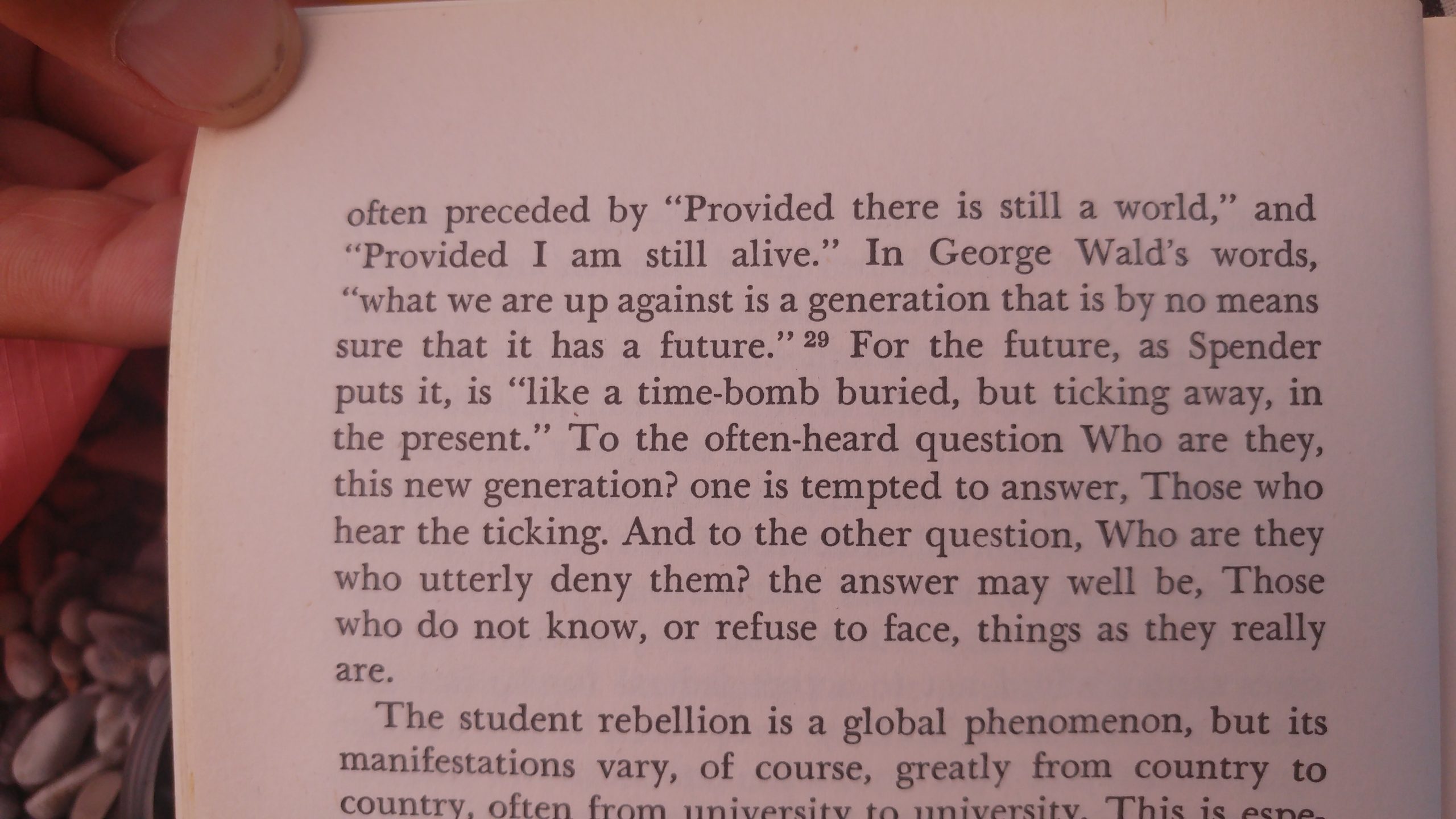

Since coming to Greece, I’d wondered what might emerge for me artistically. The slate was as blank as it could be. The proposal I’d made for the funding that was supporting my trip had been purposely open. Inspired by Cage’s words in Silence: Lectures and Writings, I’d recognised the need ‘to change one’s musical habits radically’ to really get into one’s own creative skin. But what would this mean for me? Is this what leaping before you looked felt like? I tried to let go, to allow things to unfold, hoping the conscientious intuitiveness with which I was engaging with everything I was experiencing, would yield something. And looking back to that time, I recognise how important the space of Greece’s natural wildernesses was- these walks, these times outside and away from people. It was on such a walk that I first considered making the Aeolian harps that became the key artistic focus of my time away. And it was Evia’s heights and windfarms that inspired their first flight later that summer. As Cage continues, ‘This psychological turning leads to the world of nature, where gradually or suddenly, one sees that humanity and nature, not separate, are in this world together; that nothing was lost when everything was given away’

The morning after our night under the stars, we took a path from a crease in the road, bound for the half-moon beach at Nautiko. We thought it would be just a stroll- I’d even considered wearing my sandals. A marking on the map was unclear about the distance, and what we’d thought would be a 3 hours round trip became a 7+ hours marathon, where we got repeatedly lost, didn’t see another soul on the path all day, were thrilled by the craggy coastal landscape, the high paths among aromatic riches of thyme, sage and mint which filled our senses in the warm sunshine, stunning cliff formations, orangey-red and resonant with echoes, spectacular views down over the beach where we bathed in the clear water before setting off against the clock to ensure we made it back before night fall. With the light beginning to fade, we got lost again, and half-panicked this time, imagining a night on the mountainside in our t-shirts. Again, this place felt wild: rocky terrain dense with thorny shrubs and trees entangled us at every turn.

Finally we found the path. Too tired to speak, we drove to Kymi under the golden light of the westering sun, the high hairpin roads covered with fallen rocks and occasionally sunken at the cliff edge underlining nature’s tendency to decay and reclaim. More relieved than we could express, we found a souvlaki takeaway in the town and demolished gyros and fizzy pop. Kymi was preparing to open up its restaurants fully that coming week, welcoming the tourists which prop up a fifth of this nation’s economy ahead of international borders re-opening in June and July. We eventually camped on the beach at Metochi, having dodged numerous giant toads which dotted the roads in the darkness. The following morning was overcast and it was nice to see the quietness of the place we’d driven to in the dark. Enormous rocks. A craggy surround of high cliffs covered in parts with a wild kind of green. A horse or two on the seafront. No people. Before leaving we collected two large bags of litter from the beach- fishermen’s bits, plastic bottles, floats, strings, wheels, hoping to leave the beach in an even more beautiful state than we’d found it.

On the way home, we spotted something on the road, and realised it was a tortoise. I was always delighted to see tortoises, one of Greece’s most enigmatic native species and symbolic of the Greek god Hermes, a deity said to occupy the boundary between life and death, a psychopomp responsible for guiding souls into the afterlife. Rustling in the undergrowth on our walks, tortoises would make an unmistakeable sound as their large shells pushed through the leaves. And sometimes- as on this occasion- we would also see them on the road. But this time something felt wrong. We slowed to a stop, and I got out of the car to go and move the tortoise out of harm’s way. But as I approached, I saw the road surface was covered with large bright red splotches of blood. Part of the tortoise’s shell had broken off and its red and purple insides were oozing out. Though it had been walking, its head had dipped now a little, and it was still. As it sensed me close, it tried to walk again. A bird of prey circled overhead. Stricken, I looked back at J. Another car had drawn up behind ours and he motioned to me to do something. I bent down and picked up the tortoise in my hands and carried it to the brush at the edge of the road and placed it carefully down. I don’t know what happened to it next. I just felt an animal sense of its dying. The universality of that panic for life. I felt it. I cried for a long time in the car afterwards, and cried every time I thought of it in the days afterward. That it was still trying to walk. With part of its shell gone. With its blood all over the road. This precious charismatic animal whose body takes so long to form and which lives for so long, just trashed there, its little wizened head bent forwards, its eyes dull. It isn’t life then death, I’d thought. There is a period of dying, even if death is sudden and violent. I had no connection to this animal apart from this deep moment of witnessing, and still for days later I was thinking about it.

My time in Greece was characterised by seismic global events. We are all living through them still and know what they are. The trauma of the coronavirus pandemic is close and ongoing, and is yet a ‘cuddly toy’, according to Arundhati Roy, when compared to the realities of climate breakdown. In a letter to the papers I’d stumbled across that June, Jem Bendell had written, ‘it is time to acknowledge our collective failure to respond to climate change, identify its consequences and accept the massive personal, local, national and global adaptation that awaits us all’. There wasn’t an answer, for me, artistically, during my time away. Sometimes all I could hear was the ticking. But I knew that as I began to make the drawings for my first Aeolian harps, it wasn’t only the music I’d listened to and the books that I’d read that filled the page. It was the dying tortoise, it was the empty Acropolis, it was losing the path and finding it again, it was being alone, unprepared and not knowing what to do next, it was the colour of the sky, the colour of the sea, it was everything. By the end of my time in that wild place, I knew myself better as a maker and a wild thing.

Quinta is a London-based music-maker and multi-instrumentalist. Part of a new movement of independently-minded experimental female cross-over artists making work at the intersection of art music, electronics, the DIY, visual/video art, and pop, Quinta is particularly interested in improvisation, electronic interfacing and new instruments. She works to present musical material in visually imaginative ways, using movement, dance, light, and homemade instruments and sample sets. Working across a number of fields including dance, circus and film, she has a richly diverse biography of collaborations, including with flagship contemporary dance company Rambert, pioneering ‘paperteers’ The Paper Cinema, acrobat troupes Mimbre and Ockham’s Razor and all-female arts collective, Collectress, with whom she has worked for nearly 20 years. With a background in third sector activism, Quinta is co-founder of Music in Detention and spent formative years working with Music in Prisons and participatory film-makers, Living Lens. On the back of her solo live art show The Shape Of The Moving Air (Athens 2020) and a year of international residencies supported by the PRSF Composer Fund, Quinta released Aeolian Mixtape – an album of Aeolian harp music- with Nonclassical in November 2022. She recently collaborated with award-winning BBC Essential Mix DJ HAAi and with Radiohead’s Philip Selway on their upcoming album releases, and with survivor/activist/theatre-maker Viv Gordon on the next stage of arts activism project, Restless.